Sabbaticals give faculty members a chance to conduct research, write books and articles, and develop curriculum. Here’s how this long-standing and often misunderstood academic tradition benefits Carleton faculty members and students.

During the summer of 2012, political science professor Al Montero spent almost four weeks in Brazil. His itinerary took him to half a dozen cities in the country’s northern region. But this was no vacation. Montero was on sabbatical and researching clientelism—the exchange of political support for material goods and services. He was in Brazil to interview politicians and party officials and to see firsthand the impact of clientelism on a political system.

During the summer of 2012, political science professor Al Montero spent almost four weeks in Brazil. His itinerary took him to half a dozen cities in the country’s northern region. But this was no vacation. Montero was on sabbatical and researching clientelism—the exchange of political support for material goods and services. He was in Brazil to interview politicians and party officials and to see firsthand the impact of clientelism on a political system.

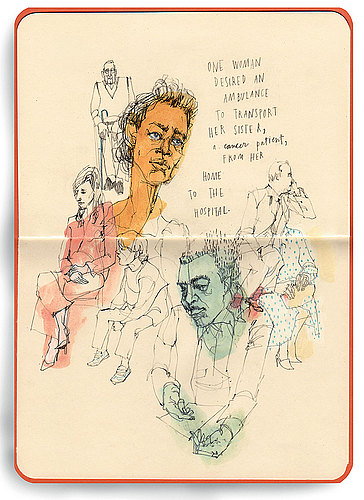

“I often had to wait to meet with these important men and women,” Montero says. “And while I sat in their waiting rooms, I was able to talk with Brazilian citizens who were there hoping to meet with the president or his assistant, because they needed something.” Some were seeking political favors. Some wanted help accessing state services or getting into vocational programs. One woman needed an ambulance to transport her sister, who had cancer, from her home to the hospital.

“In addition to doing interviews, which gave me very rich data, there was the benefit of just being in that place,” Montero says. “It gave me a sense of the very real issues that I’m studying.”

Montero and his colleagues say that in-depth research is usually possible only during a sabbatical leave. Released from teaching duties and office hours, professors can focus instead on research, writing, and creative work. “Sabbaticals are the way we carve out possibilities for faculty members to engage in scholarship,” says Carleton president Steve Poskanzer. “At a large research university, professors teach less and devote a larger portion of their day to scholarship. We don’t do that here. We have substantial teaching loads, and the sabbatical is how we allot time for scholarly, academic, and intellectually refreshing activity.”

Poskanzer acknowledges that sabbaticals are not without costs, but he sees them as an investment the college makes in its faculty. There are financial costs: paying professors’ salaries and benefits while they’re away, and salaries for temporary or adjunct faculty members. And students may need to adjust their schedules if courses taught by professors who are on leave are not offered.

At its core, Carleton prides itself on the quality of its faculty members and their focus on students and teaching. Investing in sabbaticals helps the college ensure that faculty members remain at the top of their game—and that translates into a better classroom experience for students.

The Rule of Seven

Sabbaticals are a long-standing tradition at many educational institutions. Harvard led the way in 1880, when it initiated a policy that allowed faculty members to go on leave at half pay every seventh year. (The term sabbatical is linked to the Hebrew word shabbat, which means day of rest. Religious scholars may note the importance of the number seven in the Bible. Leviticus 25 forbids farmers from working their fields every seventh year, thereby restoring the vitality of the soil.) By the 1930s, 178 American educational institutions had adopted the idea. Today, sabbaticals are offered even in nonacademic professions, including the ministry and business.

Few Carleton professors would describe a sabbatical as a period of rest. But shifting gears from teaching to research allows them to focus their energies in a different way, and that often brings a sense of respite and refreshment. “There’s precious little time for reflection during the academic year,” says French professor Scott Carpenter, who was last on sabbatical in spring 2013. “Our schedule is unforgiving. We have to be in class on certain days at certain hours, on our game, and prepared. That can be pretty fatiguing. So, when I’m on sabbatical, I have the luxury of waking up in the morning and working on my own project.”

Few Carleton professors would describe a sabbatical as a period of rest. But shifting gears from teaching to research allows them to focus their energies in a different way, and that often brings a sense of respite and refreshment. “There’s precious little time for reflection during the academic year,” says French professor Scott Carpenter, who was last on sabbatical in spring 2013. “Our schedule is unforgiving. We have to be in class on certain days at certain hours, on our game, and prepared. That can be pretty fatiguing. So, when I’m on sabbatical, I have the luxury of waking up in the morning and working on my own project.”

Carleton offers sabbaticals with full pay and benefits to tenured and tenure-track faculty members after nine terms of teaching (the equivalent of roughly three years, based on the college’s trimester system). In some cases, faculty members arrange to take two trimesters—or even an entire year—off from teaching at reduced pay, says Bev Nagel ’75, dean of the college. Such cases, however, are rare.

Nagel works with departments to minimize costs and complications associated with sabbaticals. “We don’t automatically replace a professor who is on leave,” Nagel says. Department chairs occasionally delay sabbaticals to ensure that they have enough faculty members to cover popular or essential courses. If juggling faculty and course loads isn’t possible, adjunct instructors are sometimes hired. Roughly 25—out of 190 tenure and tenure-track—faculty members are on sabbatical at any given time.

Eligible faculty members apply for sabbaticals, indicating how they will spend their time outside the classroom and how their activities will contribute to their professional work at Carleton. Applications are reviewed and approved by the appropriate department chair, by the dean of the college, and, ultimately, by the college’s Board of Trustees. In the five years Nagel has served as dean, she says, “I have yet to see an unworthy application.”

Each Carleton professor uses his or her sabbatical in a unique way, but a common purpose underlies all the leaves: furthering research. Sabbaticals provide the time to read books and journals, conduct experiments, learn new languages, develop theorems, and do fieldwork. Engaging in research ensures that Carleton professors keep current in their disciplines and allows them to contribute to the overall expansion of their fields.

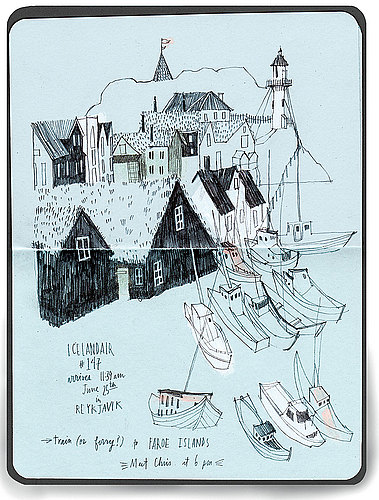

Many use their sabbaticals to travel, as Montero did. Cinema studies professor Jay Beck went to Spain to meet with directors and filmmakers. But it was a few days’ travel in the countryside with his wife that proved most beneficial. “The regional identities became very apparent to me,” Beck says. “It changed my view of Spanish film.”

On a recent sabbatical, history professor Bill North went to Lambeth Palace Library in London to translate a scholarly medieval text, set on parchment and kept in large folios. “It’s all very well to say that you should be able to do research while you’re teaching,” North notes. “But there are many kinds of research that can’t be done in Northfield.”

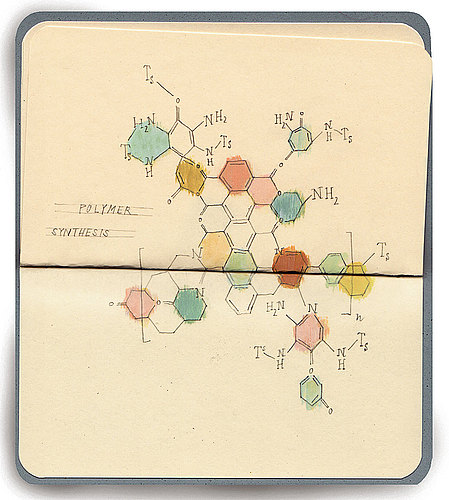

For scientists, sabbaticals can be vital to learning new protocols and developing skills with new equipment. Physics professor Martha-Elizabeth “Marty” Baylor spent a sabbatical in Colorado last fall, learning optical and chemical characterization techniques for light-sensitive polymers, and interacting with researchers who had specialized knowledge.

Other faculty members use sabbaticals to expand their professional networks and explore opportunities to collaborate—which are increasingly important in an era of cross-disciplinary studies. Linguistics professor Cherlon Ussery traveled to Sweden to meet a professor who shares her academic interests—igniting a discussion, she says, that could lead to joint appearances at conferences and cowriting papers. The slower pace of sabbaticals is conducive to developing such relationships, Ussery says: “I’m in a totally different gear.”

Even when faculty members remain on campus, time away from teaching is invaluable. Clara Hardy, a classics professor and current chair of the Carleton faculty, used one of her leaves to get up to speed in a new field: drama. “That would have been essentially impossible if I had been teaching,” she says.

Research for Students’ Sake

At most colleges and universities, sabbaticals are focused primarily on publishing and research, which are vital considerations when it comes to promotion and tenure. But critics of sabbaticals suggest that the emphasis on research is misplaced. In their book Higher Education: How Colleges Are Wasting Our Money and Failing Our Kids—And What We Can Do About It, authors Andrew Hacker and Claudia Dreifus suggest that paid sabbaticals should end: “Why should students pay for time when they won’t be seeing their professors, especially when the chief motive for publishing is to enhance personal careers?” They go on to argue that professors should write books and do research during summers and on weekends if they’re “burning” to do so.

But research and good teaching are inextricably linked, says President Poskanzer. “We’re not trying to compete with Harvard and Yale. We’re not a research university,” he says. “But you can’t stay a great teacher over the course of your life if you are not engaged in a thoughtful way in the production of knowledge and the exploration of where a field is going.”

Research also puts professors on the same side of the podium as their students. “Some of it is about the model we’re trying to set,” notes Carpenter. “In the liberal arts environment, we teach our students to be lifelong learners, so it’s important that we practice what we preach. You want to be at the cutting edge of your discipline and the discipline is always changing.”

Adds North: “Conducting research keeps you engaged in your field. You’re pushing and searching and reading the latest research. And that shapes what and how you teach. It keeps our classes fresh.”

Through sabbaticals, Carleton administrators demonstrate to the faculty that they support research

Through sabbaticals, Carleton administrators demonstrate to the faculty that they support research

and rejuvenation. And when it comes to hiring new faculty members, sabbaticals—which aren’t offered at every institution or are provided only on a competitive basis—are a perk that proves attractive to job candidates. “If we did not have a sabbatical policy, we would have a difficult time attracting the kind of faculty we want to hire,” says Nagel.

But how do the benefits of sabbaticals trickle down into the classroom? “I don’t know that there’s a trackable effect between the learning outcomes of students and the research produced by the faculty in a narrow one-to-one kind of way,” says Hardy. But she has no doubt that faculty members who keep up in their fields make better teachers than those who do not.

Carpenter concurs: “The last thing you want is someone coming into the classroom with a stack of yellowed pages, puffing the dust off them, and saying, ‘OK, I’ve been teaching this class for the past 20 years and you get to hear the same thing that students who were here 20 years ago heard.’ ”

The benefits to students are self-evident, says chemistry professor Will Hollingsworth, who studies gas-phase molecules. A student’s questions about ozone depletion was the trigger that led Hollingsworth to spend a sabbatical at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he worked with one of the leading experts in the field, Mario Molina, who later won a Nobel Prize for his research on this environmental issue.

“My time at MIT changed how I talked about ozone depletion in my introductory chemistry classes,” says Hollingsworth. “I’m able to discuss it with students in more depth, with more background.”

But it isn’t just new information that makes sabbaticals important. It’s also the perspectives and fresh viewpoints. Research conducted on sabbaticals can be challenging and demanding, notes Baylor. “But there is something very special that you learn about yourself when you are forced to confront a problem that doesn’t have clear answers,” she says. And that, in turn, creates empathy for students.

In fact, the true value of a sabbatical may not lie solely in the expansion of research, says religion professor Lori Pearson. Time away from teaching helps professors expand their ideas of what they—and their students—are capable of doing. “Going on sabbatical reminds me that I, too, am a student of religion and not just a teacher of religion,” Pearson says. “Sabbaticals give you the space to refuel. And that translates into more sophisticated, effective, and energetic teaching.”