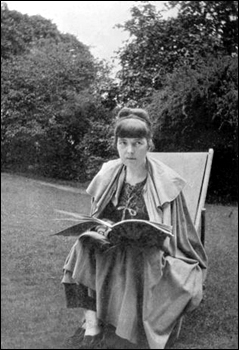

Katherine Mansfield

The photo, taken in 1916 by an unknown photographer, and borrowed from the

web site of the Katherine Mansfield Birthplace Society, is in the Alexander Turnbull Library.

Katherine Mansfield—

An overview and notes on four stories

by George Soule

A revised version of an article appearing in /Critical Survey of Short Fiction/, rev. ed. (Pasadena: Salem Press, 1993).

I

Almost everything Mansfield wrote was autobiographical in some way. A reader should know about Mansfield's life because often she does not make clear where her stories are set. For example, in "The Garden Party," readers may be puzzled by all the exotic flowers she mentions until they realize the story takes place in New Zealand.

The author was born Kathleen Mansfield Beauchamp in Wellington, New Zealand, on October 14, 1888. (During her life she used many names. Her family called her "Kass." She took "Katherine Mansfield" as her name in 1910.) Her father, Harold Beauchamp, was a businessman who rose to become Chairman of the Bank of New Zealand. He was knighted in 1923.

In 1903, the Beauchamps sailed for London, where Kass enrolled at Queen's College, an school for young women which was much like a university. She remained at Queen's until 1906, reading advanced authors such as the Irish novelist, playwright, and wit Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) and the Norwegian dramatist Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906). She played the cello. She published several stories in the College magazine, one about a lonely young girl. Her parents brought her back to Wellington in 1906, and she published her first stories in a newspaper. She left New Zealand for London in 1908, aged nineteen, never to return.

Her next decade was one of personal problems and artistic growth. She was sexually attracted to both women and men. At Queen's College she met Ida Baker, her friend and companion for much of her life. After she returned to London, she fell in love with a violinist she had known in New Zealand. Then on March 2, 1909, she abruptly married a man she hardly knew, George C. Bowden, and as abruptly left him. At her mother's insistence, she traveled to Germany, where she had a miscarriage. The Bowdens were not divorced until April, 1918.

In Germany she met the Polish translator Floryan Sobieniowski. In the opinion of her biographer Clare Tomalin, it was his fault that she became infected with venereal disease. Mansfield suffered from many medical problems for the rest of her short life: rheumatic symptoms, pleurisy, and eventually tuberculosis. Most probably were the result of this infection. Back in London, Mansfield met the editor and literary critic John Middleton Murry. Their relationship was stormy, but it endured until her death and beyond. They were married on May 3, 1918; after she died, Murry edited her stories, letters, and journals. Meanwhile, World War I had begun. Her brother, a soldier with the British Army, was killed in France. His death and her own worsening health were probably strong influences on her stories.

She and Murry knew many famous writers and artists, particularly those who gathered at Garsington, the country estate of the famous hostess Lady Ottoline Morrell (1873-1938). There she met the biographer Lytton Strachey (1880-1932), the novelist Aldous Huxley (1894-1963), the economist John Maynard Keynes (1883-1943), and the poet T. S. Eliot (1888-1965). She and the novelist and feminist Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) had an off-and-on friendship and professional association. She had a serious relationship with the mathematician, pacifist, and philosopher Bertrand Russell (1872-1970). The Murry's closest friendship was with novelist D. H. Lawrence (1885-1930) and his wife Frieda; the character "Gudrun" in Lawrence's Women in Love is said to be based on Mansfield. Both Woolf and Lawrence were influenced in their writings by Mansfield; both made nasty remarks about her before her death.

When she was in Germany, she read stories by the Russian author Anton Chekhov (1860-1904). His influence has been seen in some of the bitter stories with German settings that were collected in her first book, In A German Pension (1911). For the next seven years, Mansfield experimented with many styles and published stories in journals such as New Age, Rhythm, and Blue Review. Her first truly great story, "Prelude," was published as a booklet in July, 1918, by Virginia and Leonard Woolf's Hogarth Press.

Her health continued to get worse. From the time she learned she had tuberculosis in 1917, she spent most of each year out of England. Accompanied by Murry or Ida Baker, she traveled to France, Switzerland, and Italy, trying to fight off her disease. In 1922, her search led her to a kind of rest home near Paris. She seems to have been moderately happy there until the end. She died at Fontainebleau on January 9, 1923.

During her last five years, she wrote most of the stories for which she is best known. They were often published in journals such as Athenaeum, Arts and Letters, London Mercury, and Sphere. Many were then collected in Bliss and Other Stories (1920) and The Garden Party and Other Stories (1922).

II

Mansfield once described in a letter two of the things that make her write. One is "joy." She said she feels joy when in "some perfectly blissful way" she is "at peace." At that time, "something delicate and lovely seems to open before my eyes, like a flower without thought of a frost." Everywhere in her work she communicates the exhilarating delicacy of the world's beauty: "A heavy dew had fallen. The grass was blue. Big drops hung on the bushes and just did not fall."

Her second motive is almost the opposite: "not hate or destruction . . . but an extremely deep sense of hopelessness, of everything doomed to disaster, almost willfully, stupidly." She summed up her second motive as "a cry against corruption. . . . in the widest sense of the word." We see such a cry in her story "Je ne parle pas francais." There we meet an amiable young Frenchman who seems to be a sympathetic friend to a young Englishman and his intended bride. But the friend slowly reveals himself as depraved, a heartless gigolo and pimp. More frightening is the central character of "The Fly." He is a businessman who grieves when he remembers his son who was killed in World War I. He appears unpleasant when he treats an old employee badly, but the readers do not understand the full horror of the story until he sadistically tortures and kills a fly who has landed in his ink pot.

Not all hopelessness in Mansfield's stories is so narrowly corrupt. Mansfield continually shows us the yearnings, complexities, and misunderstandings of love; men and women spar at cross-purposes. Sometimes they fail to love because they are timid. Sometimes one person rejects another because he or she simply has more important goals to pursue. Sometimes the rejected person is sick or old. In one story, appropriately titled "Psychology," a male and a female artist are so painfully self-conscious of the ebb and flow of their relationship that they cannot get together. Finally, in some stories, individual yearnings are complicated by sexual confusions with homoerotic overtones.

Society is corrupt and stupid and destructive. Mansfield is brilliant when she renders the vapid conversation of fashionable, artistic figures. They prattle on about the latest fashions or recite silly poems, while ignoring the dramas of real feelings that are going on around them and destroying the lives of better people than they. She is equally brilliant in portraying the banalities of more common people. Even when they mean well, many characters cannot say anything that makes a difference.

Not all corruption involves blame. Mansfield sees that life itself seems corrupt when we realize how many people are failures. We see failure most vividly in the life of a lonely person, often a woman, playing a guitar with no one to hear, looking out of a hotel window, writing a letter, noticing the happiness of other lovers, reflecting on what has gone wrong with her own loves. Often in Mansfield's stories, the reader senses the ultimate in corruption: the ceaseless erosions of time and forgetfulness. The natural world itself is not always consoling. Its beauty is sometimes frightening and ominous. Its power, especially the power of the sea, can be indifferent.

Mansfield's style is economical; she has edited her prose so that there is seldom an unnecessary or insignificant word. But, although she is noted for her precise descriptions, her exact meanings are not always easy to pin down. Her tone is complex: she mixes witty satire with shattering emotional reversals. Moreover, because she uses dialogue and indirect speech extensively and does not often seem to speak directly in her own voice, the reader is not always sure what to believe.

The action of her stories does not surge powerfully forward. People talk and think; they don't ride horses or shoot rifles. Their lives don't move to climaxes in which we learn something definite. Often her stories are designed, by means of quick changes in time and by surprise turns, to lead the reader to an unexpected moments of illumination or "epiphanies." It is vital for readers to understand that Mansfield does not conceal a hidden "message" in her stories. If a story appears to point in many directions, not all of which are logically consistent, that is the way Mansfield feels the whole truth is most honestly communicated. In this she resembles Chekhov, to whom she is often compared.

Mansfield's descriptive passages repay careful attention, for they are always significant. Her descriptions are always more than a mere record of what New Zealand or England was like. For example, in one story a young girl visits an empty house and finds only "a lump of gritty yellow soap in one corner of the kitchen window sill and a piece of flannel stained with a blue bag." This is not a very pretty picture, and it suggests that the girl is unhappy to leave, unhappy that her home has been reduced to such ugly things. Mansfield has given us details that a girl would notice and that suggest to us what the girl is feeling. During the years Mansfield was writing, new poets like T. S. Eliot (1888-1965) tried to give the reader, not statements about emotions, but concrete details which would act like an "objective correlative" of those emotions. Like them, Mansfield does not usually tell us what her characters feel. She presents details that will make us feel what they feel.

Sometimes, however, at very important moments, Mansfield's details become even more suggestive or symbolic. On one hand, the sea can suggest the power of time. On the other, a girl's party hat in a room with a corpse suggests the frivolity of another place. Often, Mansfield builds trees into symbols. Both the pear tree in "Bliss" and the aloe tree in "Prelude" must be considered both as natural details in the situations of the stories and as symbols. What they symbolize is not simple an arbitrary idea--such as hope or death. Each tree is different, and what it symbolizes can only be understood as we read each story.

As noted above, Mansfield's finest stories are also characterized by "epiphanies." That term, popularized by the Irish novelist James Joyce (1882-1941), refers to a sudden revelation which is triggered by an ordinary experience. In Mansfield's stories, epiphanies can happen to characters. And they can be created for readers by the way the author leads us to an unexpected moment, as when we realize that a silent, wretched little girl has remembered not that she has been treated badly by a snobbish woman, but that she has seen a tiny lamp in a doll's house.

III

"Miss Brill" (1920) is one of Mansfield's many lonely women. Hers is the story of a Sunday afternoon in the autumn. A chill is in the air. In her room, Miss Brill, an English teacher, prepares to go as usual to the Public Gardens in what appears to be a French city. She happily unpacks the fur she will wear for the first time this season--a fur piece which includes the head of the small animal, perhaps a fox. She strikes the reader as imaginative, for she pretends she hears what the dead animal is thinking after being in storage for many months. Then she feels a tinge of sadness, something she calls gentleness. In her introductory paragraph, Mansfield's details evoke the fragility of Miss Brill's happiness.

At the Gardens, Miss Brill listens to the band play and watches the people. Though she yearns to talk to them, she must be content to listen. An old couple disappoints her, for they are silent; last week she heard a memorable conversation about eye-glasses--memorable to her, but trivial to the reader. Then Miss Brill takes her first step away from the surface of the afternoon. She reflects that most of the people she sees here are old and strange. We sense she hopes for their happiness.

In a typical surprise, Mansfield suddenly gives us two very short paragraphs. The first points beyond the gardens to the sky and sea, as if to suggest there is a wider world than we have experienced so far. The second brings us back to the banality of the park, as it reproduces the tum-tums of the band.

Miss Brill's experience deepens. She does not simply listen; she imagines what the people she sees are saying. Mansfield employs dramatic irony when the woman who Miss Brill thinks is innocently chatting actually seems to be a prostitute. Then Miss Brill stumbles on a kind of truth: they are all acting in a play. She is in the play too! She has a role, and she plays it every week. Miss Brill has turned her understanding of how drama underlies public events into a consolation for her state. Even so, she knows all people are not happy. She has a vision of their all singing together.

Mansfield has artfully brought us to feel with Miss Brill as her love flows out to all she sees. Then comes the shock. A young couple, rich and in love, sit down on the end of her bench. She hears them wonder why she sits there, wonder who would possibly want her, and compare her prized fur to a fried fish.

We have lived through the story within Miss Brill's mind. Now Mansfield lets us back off and imagine what this shock is like. Miss Brill silently goes back to her lonely room. She says nothing. But when she puts her prized fur piece away in its box, she imagines she hears a cry. Her imagination has projected her own sorrow.

"Miss Brill" is a typical Mansfield story in that it has little action. It dwells in the mind of a lonely person, as she deepens her understanding and receives a shock. The reader is drawn into sympathy with the brave, sad central character.

IV

"Bliss" (1918) begins with Bertha, a young wealthy woman married to Harry Young, in a state of bliss. The spring afternoon is brilliant, the fruit has arrived for her to arrange, her lovely baby seems happy with her Nanny, a group of sophisticated friends are coming to dinner, and her house looks beautiful. Bertha sees herself in the mirror--she anticipates something wonderful. As usual, Mansfield can evoke the wonders of being alive, and as usual, things are not quite as nice as they seem. Nanny bosses Bertha around. Bertha herself seems a bit childish. Harry will be late; when he does come he makes an abrasive remark. One guest, a Miss Fulton, is mysterious. In the garden, cats prowl (are they mating?), but a tree bodes well, a tree described with Mansfield's customary evocativeness. Bertha sees "the lovely pear tree with its wide open blossoms as a symbol of her own life."

The guests arrive, and Mansfield shows her ability to satirize the social world of poets and painters. One guest wears a dress which shows a procession of monkeys; married couples call each other by silly names; a languid homosexual playwright has had a bad experience with his taxi-driver. Harry, Bertha's energetic husband, forms a contrast, as does the cool Miss Fulton, who arrives dressed all in silver.

Up until now, the story's action has been haphazard, and we have been given few clues as to what may happen. But then Mansfield delivers her surprise, a series of events which may have shocked her readers. Bertha touches Miss Fulton's arm and feels a "fire of bliss"; a look passes between them. Through the inane dinner conversation, Bertha blissfully wonders at her experience and waits for "a sign" from Miss Fulton with little idea of what such a sign would mean.

It becomes more clear to Bertha in a moment. Miss Fulton seems to give a sign, and they go to the garden and gaze at the pear tree, that had seemed to Bertha to be a symbol of her openness and vulnerability. What exactly does it suggest now? No matter what, to Bertha, the women achieve a perfect, wordless understanding. But Mansfield is ambiguous. What have they understood? Something feminine? Something about desire? Has Miss Fulton really participated in this experience, or is Bertha imagining their epiphany?

Mansfield has more surprises. As the guests prepare to leave, Bertha takes a new course: "For the first time in her life Bertha Young desired her husband"! Not many writers could suggest how a young woman's homoerotic feelings could so quickly shift to heterosexual ones.

Then her bliss is shattered. She glimpses Miss Fulton and her husband intimately whispering together, arranging for a rendezvous, and Bertha is left wondering what will become of her life? Mansfield does not ask us to draw a conclusion. Are we to understand that Bertha is trapped in an evil world? That her happy, childish life is over? That she is a free adult at last?

V

Mansfield wrote two long short stories set in her native New Zealand: "Prelude" (1918) and "At The Bay" (1922). In both she drew extensively upon the life of her own extended family. And in both she employed an untraditional and fragmented structure which was peculiarly her own.

"At the Bay" is composed of thirteen short episodes in which a number of lives are intertwined. We are set down in an unidentified place among unidentified characters. Soon it becomes clear that the story takes place at a settlement of families living in separate houses at the side of a bay. What we know of Mansfield's life leads us to picture this as Wellington Bay in New Zealand. Because it is not clear who exactly the characters are, we are challenged to guess their relationships. That the reader must take time and effort to discover these things is part of the story, part of Mansfield's technique.

Most of the characters are relatives of the Katherine Mansfield-like character, Kezia. The reader may find a list helpful:

Kezia, a young girl, about eight years old

Stanley Burnell, her father

Linda Burnell, her mother

Isabel, her older sister

Lottie, her younger sister

a baby brother

Aunt Beryl, Linda's sister

Uncle Jonathan Trout

Pip and Rags, his sons

Mrs. Fairfield, Kezia's grandmother, Linda and Beryl's mother

Alice, a servant

Mrs. Stubbs, Alice's friend

Mr. and Mrs. Harry Kember

Each episode is separate. Usually, there are not obvious transitions from one to the next. But the reader gradually senses that "At The Bay" has a kind of unity, not radically different from that of a more conventional story. The same characters appear and reappear, though unexpectedly. The story lasts for a complete day, from early morning until late at night. Most important, all the character live in a web of delicate interrelationships, some of which satisfy, some of which do not. In the story of almost every character, we find variations on a central theme: to live is to yearn for something more than you have and only occasionally to be calm and happy. We yearn most strongly for what is seldom possible. Each character must face moments in which his or her hopes are thwarted.

The first and the last episodes frame the story with descriptions of nature. In the first, the only moving beings are a herd of sheep, a sheep dog, and a shepherd. They enter and leave. In the very brief last episode, no living thing appears. Both provide descriptions of the bay, the sea and the waves, and the plants and buildings on the shoreline. The first episode sets the scene as a peaceful but vibrant place that seems to wait for what the day will bring. The second is more obviously symbolic. The seaeternal changeis briefly troubled by what has happened, but only briefly.

The day opens with Stanley Burnell taking an invigorating swim. He is the most masculine force in the story, competitive (he's happy to think he is first in the water) and forceful. But Stanley finds another man, Jonathan Trout, has beaten him to it. Trout is as good a swimmer as Stanley, but more imaginative, less pushy. No wonder Stanley is irritated and leaves. Trout muses on the encounter: poor Stanley makes work out of pleasure, he thinks. The episode ends with a suggestion that Trout is not in good health. Mansfield begins her story with its only adult males, each of which is severely limited.

Episode three shows us the Burnell household while Stanley gets ready to leave for work. This scene shows Mansfield at her best in evoking many different lives at the same time. Stanley is the center of the action. He questions, accuses, blusters, and irritably orders everybody about. He is the man of the house leaving for work, and everyone must know it. But just as he climbs onto the coach that will take him away, he notes that his sister-in-law Beryl, though obedient, has her mind elsewhere. The reader has suspected all along that Beryl has some private secret, and all the other women have their secrets as well: the child Kezia has her own way of eating porridge, Isabel is full of virtue, Mrs. Fairfield abstractedly responds to the beauty of the sun's illuminations, Linda's mind is miles away, Alice exclaims against men in general. Beryl feels that the women have a kind of communion after Stanley is gone--the wonderful day will be theirs. But her mother and sister do not seem to share this feeling so ecstatically.

Succeeding episodes develop the various strands of the story belonging to the children, the servant Alice, Mrs. Fairfield, Beryl, and Linda. By constructing her narrative in parallel stories Mansfield insists on the separateness of individual minds and the problems we have in communicating to each other. But by having characters cross over from strand to strand and by showing parallels in their lives, Mansfield implies that people's lives have much in common.

As usual on a fine morning, the Burnell girls go to the beach, where they play with their boy cousins, the Trouts. Later, they regroup inside for a childish card game. The girls bicker; the whole group is dominated by Pip, the oldest Trout boy. We see sexual tensions beginning even at this age. . . . Sexual tensions are also the point of the servant's visit to a Mrs. Stubbs, a storekeeper. Mrs. Stubbs frightens her by saying she prefers being a widow. . . . Kezia confronts something else when she spends her afternoon siesta with her grandmother. Mrs. Fairfield has the wisdom of age; though she still aches for her dead son, she is resigned. When Mrs. Fairfield tells the girl of this death, Kezia rebels: Kezia will not die, and she demands a promise that her grandmother will not die either.

Linda is Mansfield's most enigmatic figure. She strikes everyone as listless, vague, and detached. She and her mother are adults; they seem to be past yearning. We often live in her mind, and we see her chiefly in relation to three males. With Jonathan, her brother-in-law, she listens sympathetically though distantly to his complaints about his weakness and his fate. Her attitude toward Stanley is more complex. She remembers transferring her affections from her adored father to Stanleyloyal, loving, tongue-tied, uncomplicated, sincere Stanley. She loves him, but resents having to support him as you would a big child. Her listlessness appears to be the result of her children. She dreads having more, and does not love the ones she has. Then, in a moment in the center of the story, she looks down at her baby boy. For a moment, she may love him.

Beryl is younger than Linda, in years and in experience. Mansfield may be suggesting that the sisters and their mother show three stages in women's lives. The young Beryl is secretive with Stanley, impatient with Kezia at breakfast, and vibrant with hope in the morning. Her crisis begins at the beach as well. There she meets the unusual Mrs. Harry Kember. Mrs. Kember (we never learn her first name) is married to an extremely handsome man at least ten years her junior. She must have money. Her body is long and narrow. She smokes. She plays bridge. She talks like a man. While Beryl disrobes before putting on her bathing suit, Mrs. Harry Kember teases her about her beauty. Her suggestive remarks are startling, and Beryl feels "poisoned," but she is fascinated. That night when everyone else is asleep, the aroused Beryl imagines a perfect lover. As she fantasizes, she hears a noise outside her window. It is Harry Kember himself. He persuades her to some out. She walks to him, then is horrified to see a smile on his face she had never seen before. She breaks from his embrace. Like Linda and her mother before her, Beryl finds that love is not what it seems.

VI

"The Garden Party" (1922) may be Mansfield's most famous story. It is exceptional and typical at the same time. We have a vibrant young woman (Laura) as the central character. We have a sophisticated older woman (Laura's mother) a sophisticated social gathering (the party itself), some moderately dense males, and a disturbing event to which they all react differently. The action of the story, more conventional than that of "At The Bay," is also typical of Mansfield. It leads both Laura and the reader to an "epiphany"--a enigmatic moment of revelation that is comic and overwhelming at the same time.

Unlike "At The Bay," where Mansfield took us into many minds, we live through this story in only one. Laura appears to be about sixteen, a young woman on the edge of adulthood. Not only do we hear her talk, we listen in on specific thoughts. She is a bit afraid of the men who put up the tent for the party but enjoys hearing their matey banter. We sense joy at being alive when she reacts ecstatically to the spots of light the sun makes on an inkpot. Mansfield brings us close to Laura in another typical way: even the opening description of the day and the flowers seem to be in a character's mindnot the story-teller's. To many readers, that mind soon becomes Laura's. The opening scenes all suggest a wealthy, normal, and happy family. Laura seems to supervise the tent, but the workman make the decisions where it should go. Her sisters strike sophisticated poses; one sings a gruesome song and flashes a big smile. Laura's mother protests that she will leave everything to her children, but organizes the party anyway: expensive flowers, a band, dainty sandwiches. As she often does, Mansfield suggests moments of happiness with telling details (where are the flags for the sandwiches?) and evocative descriptions.

Then comes the news that turns Laura's day around: A man has been killed in an accidenta man who lived in a lower-class cottage almost next to their home. Laura's instinctive reaction is that the party must be stopped. The man's family could hear the band from the party. Her sisters and her mother argue with her, but she does not change her mind until she sees herself in a mirrora lovely girl with a spectacular black hat trimmed with gold daisiesand until her brother Laurie compliments her. The party goes ahead. Guests compliment Laura as well, especially on her hat. When it is over, and her mother tries to make amends by filling a basket with party leftovers and sending Laura with it to the dead man's cottage.

The journey at dusk is phantasmagoric. Laura walks into a different world, a lower-class world of grieving, ill-dressed, unsophisticated people. At the house, she gives the widow her basket and then is led against her wishes to the bedroom, where the corpse was laid out. Laura sees death as something calm and even beautiful, something far removed from her silly afternoon. "Forgive my hat," she says. She has had an epiphany--a manifestation of a basic truth. The reader may have had an epiphany as well, though it is not the same as Laura's. Her reply may be been inadequate, but we have been shown a character's moment of understanding and growth.

The story ends ambiguously. Laura heads home and meets her brother. She tries to say something, but can't find the words. She thinks he understands. Does he? As usual, Mansfield does not push her case too far.

In sum, Katherine Mansfield's short stories responded to her age and showed the way to many later writers of the modern short story. Her stories do not depend upon showing a chain of actions and upon the explanations by the author. Rather they dramatize webs of personal thoughts and interrelationships and embed them in descriptive, suggestive, and even symbolic details. Her stories often lead the reader to moments of revelation, or "epiphanies." Her themes are also those of her age and were also taken up by later writers: joy in beauty, yearnings for happiness (particularly by women), disappointment, callousness, and cruelty.

Bibliography

Alpers, Antony. The Life of Katherine Mansfield. New York: Viking Press, 1980.

Alpers, Antony, ed. The Stories of Katherine Mansfield. Auckland, N. Z.: Oxford University Press, 1984.

Berkman, Sylvia. Katherine Mansfield: A Critical Study. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1951.

Hankin, C. A. Katherine Mansfield and her Confessional Stories. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1983.

Hanson, Clare, and Andrew Gurr. Katherine Mansfield. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1981.

Kobler, J. F. Katherine Mansfield: A Study of the Short Fiction. Boston: Twayne, 1990.

Nathan, Rhoda B. Katherine Mansfield. New York: Continuum, 1988.

Tomalin, Clare. Katherine Mansfield: A Secret Life. New York: Knopf, 1987.